Teaching Responsibly with AI, Webinar #1: AI and Ethics

Over 3,000 educators signed up, and 1,070 showed up live. This was the first event in our Teaching Responsibly with AI webinar series.

Over 3,000 educators signed up, and 1,070 showed up live. Hundreds shared how they’re including GPTZero in their syllabus as part of the writing process, not the final checkpoint. This was the first event in our Teaching Responsibly with AI webinar series, and it couldn’t have come at a better moment. In the past two months, we’ve scanned more documents than in GPTZero’s first two years combined. Educators aren’t just asking if something was AI-written, but what happens after the detection?

Meet the Speaker: Antonio Byrd

We were delighted to welcome Antonio Byrd, Assistant Professor in the English Department at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. As a member of the MLA-CCC Task Force on Artificial Intelligence, Antonio is at the forefront of developing guidelines and professional standards for AI use in writing instruction. His background in composition and rhetoric, combined with his work on faculty professional learning in generative AI, makes him uniquely qualified to address the ethical considerations we face as educators.

Going from Surveillance to Engagement

According to Byrd, AI detectors shouldn’t be the end of a conversation, they should be the beginning. He argues that too many educators are falling into “surveillance pedagogy”, leading with suspicion, monitoring for misconduct, and letting AI scores drive punitive decisions. He says: “I don’t want to be raising an eyebrow at my students all the time, tracking and scrutinising everything they do throughout the writing process. That’s not the relationship I want.”

Instead, he advocates for a values-based approach rooted in engaged pedagogy, a term coined by bell hooks. At its heart is the idea that students are co-creators of knowledge, not passive recipients, and that education is as much about connection and transformation as it is about information transfer.

That level of trust starts with tone. In Byrd’s own classroom, he sets the tone from day one by playing some chill hip-hop beats from YouTube. “When students come in, the music is already playing… because silence can be awkward, especially on the first day when no one’s really talking yet.”

Some use icebreakers. Some connect to students’ lives. Some greet students at the door. Someone in chat said, “Start with a story”. Someone else said, “I don’t start with the syllabus. I start with who we are, together, and then get to the syllabus later.” That’s the kind of learning tone we want to set, one built on relationship and shared experience.

All of this connects back to engaged pedagogy and how we can create authentic, trusting environments that help students feel safe enough to take academic risks and reflect on their process.

One activity Byrd uses is values affirmation, which research shows can reduce stereotype threat, especially for marginalised students. It supports academic achievement, builds a sense of belonging, and, he believes, reduces the impulse to cheat or over-rely on AI. Often, students turn to AI not out of dishonesty but because they feel overwhelmed or afraid to fail. Creating a classroom culture where mistakes are part of learning is key. Values affirmation helps foster that by modelling empathy, care, and integrity.

At the start of the term, he asks students to pick a few values (like honesty, creativity, or responsibility) and reflect on why they matter. Together, they create a shared values list, then discuss what those values look like in practice: What does constructive criticism sound like? What does friendliness mean here? These conversations do two things: they build respectful, human-centred engagement and create a framework to return to if a student misuses AI.

Instead of “You broke a rule,” it becomes, “Does this align with the values we agreed on?” From there, students can begin thinking critically about AI use in the context of their shared expectations.

The Sliding Scale of GenAI use

Rather than drawing a hard line between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” uses of AI, Byrd introduces a more flexible framework: a sliding scale of GenAI use. At one end, there’s reward to critical inquiry, such as uses that align with class values and promote learning. For example, a student using AI to generate ideas or organise sources for a literature review. These tools can spark engagement when students remain in the driver’s seat.

In the middle are pain points. These are uses of AI that don’t quite break our values, but they’re annoying or misleading. A good example is a “hallucinated source” — the student includes a reference that sounds real but doesn’t exist. Maybe AI made it up.

“For me, that’s a pain point. It doesn’t necessarily ruin the whole paper, but it tells me I need to say something. Like, ‘Hey, just so you know, these sources aren’t real. This might be an effect of using AI.’”

Then, at the far end, we have harms. These are serious violations of the values we’ve agreed on. Maybe the entire assignment was written by AI. Maybe the student wasn’t involved in the process at all.

“You’ve probably seen this before: a student hands in a paper that just doesn’t sound like them. Maybe an AI detector flags it at 99%. That’s when we’re dealing with a major breach of academic integrity. That’s when a real conversation needs to happen.”

Listening to Truly Understand

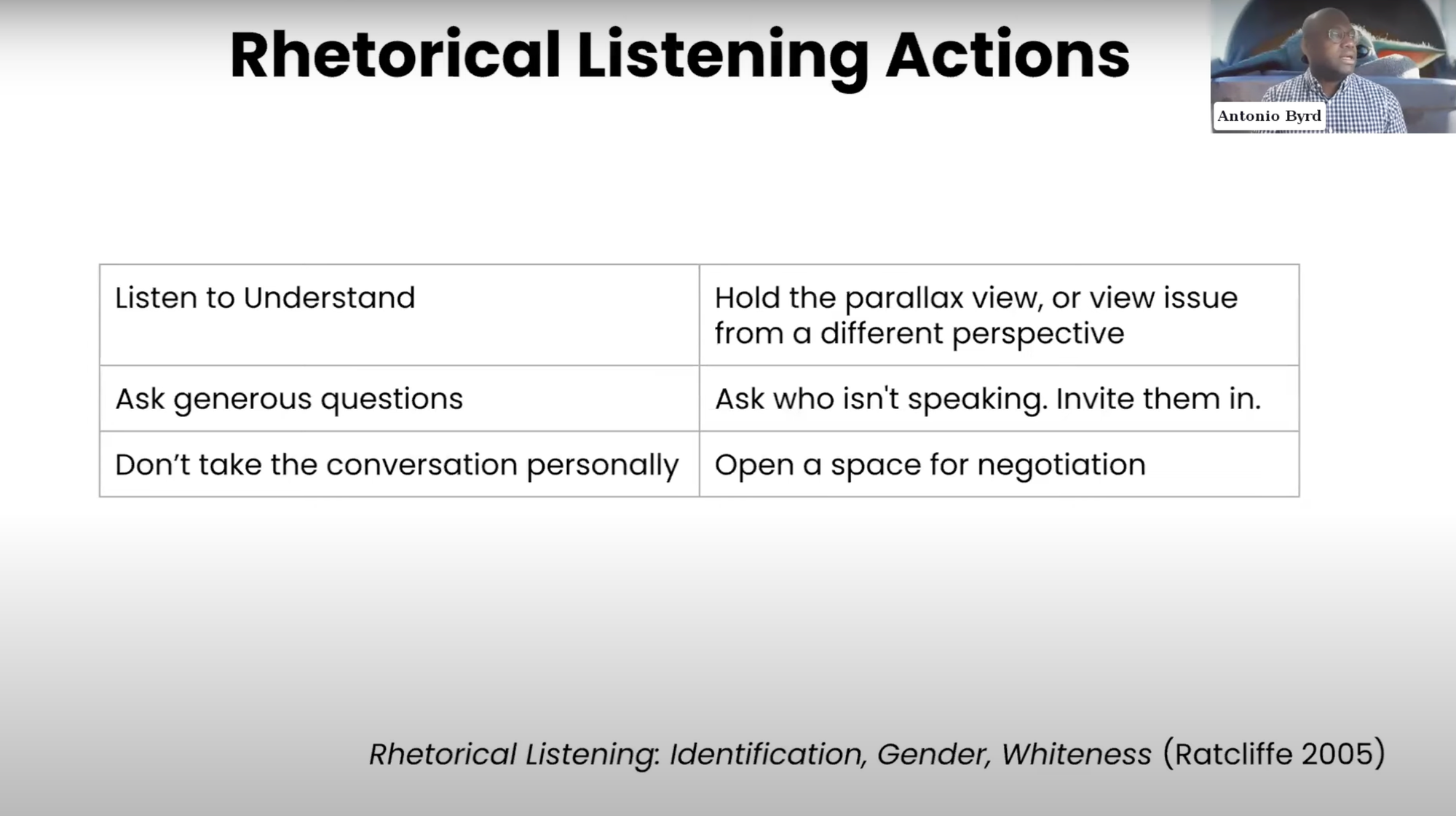

Byrd proposes using rhetorical listening as a framework for those hard conversations. It’s about listening to understand, not just to respond. Here are some rhetorical listening actions, drawn from the book Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, and Whiteness:

- Listen to understand. Not to respond. Not to defend. Just to understand.

- Ask generous questions. Not accusatory ones. Open-ended questions like: “Can you tell me about your process for this assignment?”

- Don’t take the conversation personally. If the student is defensive or frustrated, try not to internalise that. They may be scared. Confused. Caught off guard.

- Ask: Who isn’t speaking in this conversation? Are there students who feel silenced by AI policies? Are there voices we’re not hearing, e.g,. multilingual students, neurodivergent students, marginalised students? Make space for them.

Byrd shared a real-world scenario: a student submitted a generic literacy narrative, and the style copied what an AI chatbot produced when given a similar prompt. Rather than file a complaint, the instructor commented on the lack of detail and suggested revisions, especially since it was still a draft. “You don’t need to accuse them,” Byrd said. “Just give honest feedback. And because they’re still in the revision stage, they’ll have to rewrite anyway.”

Making It Scalable

For teachers facing large classes or limited time, Byrd offered several practical alternatives to one-on-one conversations:

Ask students to annotate their drafts

Ask students to annotate their drafts, explaining what each paragraph is doing rhetorically. “This forces students to engage with their work critically. And if they did use AI, it pushes them to wrestle with that text as their own,” he said.

Set an AI-detection threshold for revision

Set a transparent threshold – say, 20% probability on an AI detector, that triggers a revision request, not a penalty.

Use self-assessments and metacognitive prompts

Invite students to reflect on what tools they used, what they learned, and what they'd do differently. This shifts the conversation away from “gotcha” detection and toward learning as a process, which is especially important when teaching writing.

These strategies all share a common principle: they prioritize process over product, support student reflection, and scale well for large or asynchronous classes. Yes, they take some initial setup and require the teacher to model the approach. But over time, these small shifts help build a classroom culture grounded in authenticity rather than surveillance.

A Culture Where Learning Still Happens

Finally, Byrd advocates for a cultural shift. If students are to meaningfully reflect on their relationship with AI, the focus has to move away from grades and punishment and toward authentic learning. That means helping students go from “I just need to get this done and get the grade” to “What am I learning here? How is this process changing me?”

This won’t happen overnight and won’t come from a single policy. But it can begin with small, intentional teaching strategies, the kind James Lang describes in Small Teaching. Lang argues that we don’t need to overhaul our courses to be effective. We just need to make intentional, strategic shifts that support deeper engagement.

Byrd leaves us with this: educators don’t need to rewrite their entire curriculum or become AI experts overnight. But they can make small changes that centre reflection, relationships, and values. “And these small changes really do matter. In a world where generative AI is everywhere, it’s our job to ensure that learning still happens, and that students see the value in doing things thoughtfully, ethically, and with intention.”

Watch the entire replay here.