Is “Bypass Culture” Changing the Way Students Use AI?

New AI tools are changing how students complete assignments and reshaping how they think, prompting the question: What does learning mean now?

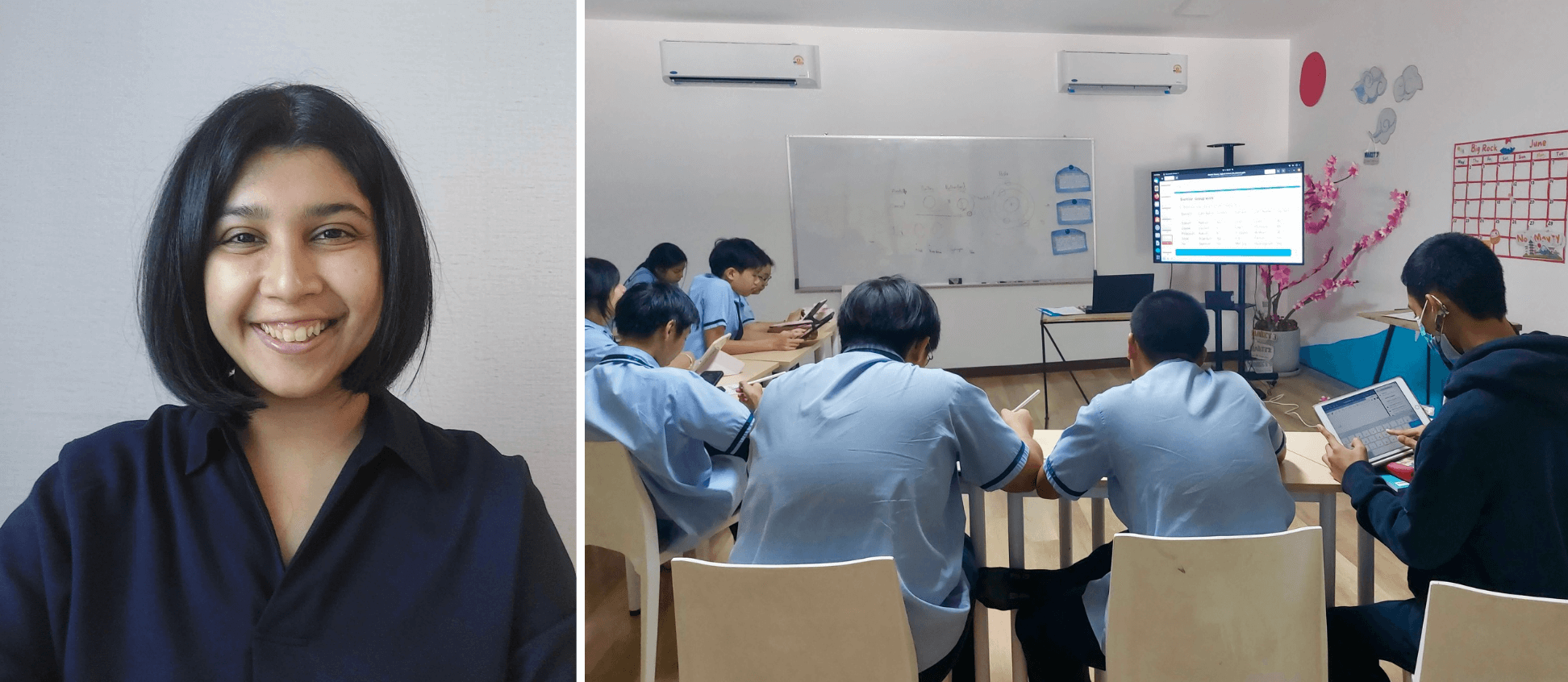

In a classroom in Thailand, mathematics teacher and GPTZero fan Humayra Mostafa noticed something strange: her carefully designed homework assignment had led to massively inconsistent answers. Although she had verified her own solutions using AI, the tool had generated a different set of responses. Then it hit her: the AI hadn’t made a basic math error. It had confused her exercise with a similar one from a different source.

“When I shared the exercise with my students as homework,” she recalled, “I discovered that four of them had done the same thing and submitted the wrong homework. That is when the realization hit me - students do not have the awareness that AI can make mistakes.”

Mostafa’s experience demonstrates a larger, growing shift in education: “bypass culture” is where students are using AI to sidestep the learning process altogether. Rather than working through problems or developing their own voice, students are increasingly handing over the heavy load to AI tools.

With AI, What’s the Point of Learning?

While many students still turn in complete work, more and more often, the critical thinking that should underpin that work is missing. The rise of generative AI has made it easier than ever to produce answers that look polished, even when the process of learning has been skipped entirely.

“I believe communication is important between the teachers and the students so that students understand the goals and intentions of learning,” said Mostafa, who has been teaching for seven years and currently works as a foreign teacher in Thailand. But lately, she’s been fielding a new kind of student question: Why learn at all, if AI can do it?

“The first case is that I am facing queries from my students: ‘Why do I need to learn Math if AI can do it?’ Also, sometimes my students tell me that his/her friends are using ChatGPT to get the homework done.” In bypass culture, AI represents a shortcut that replaces effort with automation.

The second issue is even more subtle. When asked to research topics (e.g., the protein content in 100 grams of chicken), her students would turn to AI-generated overviews and copy the information without checking the source.

“Then students will just Google it, see the AI overview, and copy the information from there without verifying sources,” she said. The result is incorrect answers and a disconnection from the why behind the task, not to mention the loss of practice in the basic academic skills of evaluation and judgment.

Learning still means taking in new information, but with AI, the pace and the point of learning can start to evolve. While AI can change the speed of access to information, it does not take away the necessity of discernment. And this is where forward-thinking educators are now stepping in, to teach students how to use AI tools with critical awareness.

The Illusion of Accuracy

Mostafa was an early adopter of AI tools. “I had an early intuition that AI would become an efficient tool and early adopters would have an advantage. So I started learning as much as I could.” But her experience with mismatched AI answers served as a turning point.

“I realized the AI overview had based its response on a similar-looking exercise (at that time, ChatGPT did not have the feature of attaching files yet). The first few questions were the same, but the last three were different. This caused a mismatch in the last three answers.”

Her students had done what many are now doing: trusting the first AI answer they see, which can be efficient and easy, but not always accurate.

“That is why students blindly copy from AI without verifying and submit the wrong assignments,” she said. “They don’t understand that data can be biased, incomplete, or that AI generates inaccurate information. And that AI tools often use pattern recognition for the given content, and this can result in wrong answers.”

Across the world, teachers are observing a similar pattern: students leaning heavily on AI to produce outputs without engaging in the underlying process. The phenomenon was captured recently in a New Yorker article by Hua Hsu, who observed that many students now rely on AI to summarize reading material and even think on their behalf.

This is why it is crucial for teachers to show students how AI tools sound confident, but are not always accurate. It is being able to gauge that accuracy that matters; because without that ability, students risk mistaking fluency for truth.

Teaching AI Literacy

The instinct in some academic circles has been to police this behavior, to ramp up detection tools, and create stricter guidelines. But Mostafa sees a different path forward.

“I give the freedom to my students to use and learn from AI as a tool for improving their work,” she said. “Because I want students to navigate the world of AI that the future has to offer.”

“From my understanding, for that we need to differentiate what is AI-generated work and what is human work,” she continued. “As a result, I believe software like GPTZero plays an important role in helping students to learn to use AI effectively rather than to copy blindly.”

In her classroom, discernment is the goal, not punishment. And that means helping students understand what these tools are, how they work, and where they fall short.

“Students should learn to distinguish between human-written and AI-generated content,” she said, “so they can evaluate the credibility and perspective of what they are reading.”

Recently, Mostafa led a discussion with her students about a list of “50 books to read this summer” - a viral article that, as it turned out, had been entirely generated by AI, which in itself became a teachable moment.

“We had an open discussion about it,” she said, “and the students concluded on their own that the contents must be verified, without much intervention from me.”

It’s these conversations that make AI literacy stick, by going beyond punitive rules and moving more into reflective thinking, giving students the confidence to evaluate, question, and push back on AI-generated content.

What Educators Can Do

So, what does all of this mean for educators? To tackle these questions, GPTZero recently ran its inaugural webinar series, Teaching Responsibly with AI. The series brought together educators from across grade levels and disciplines to share how AI is reshaping classroom dynamics.

We explored, among other issues, how to communicate AI policies clearly in syllabi and how to empower students to use AI thoughtfully rather than blindly. It was in this series that Humayra first heard about the now-viral AI-generated “50 books” list, which later sparked a classroom discussion on source credibility.

Several educators in GPTZero’s teaching network have started embedding AI guidance in their introductory course emails (check out one example here). Instead of waiting for students to misuse AI, they’re proactively offering frameworks for responsible use, giving students a head start in navigating these new tools thoughtfully.