The Official AI Survival Guide for Teachers

How do you teach in a post-ChatGPT world?

Teaching has always been demanding, but generative AI has introduced a whole other element to the classroom. All around the world, teachers are asking: how do I design ChatGPT-proof assignments? How do I set rules around AI in the classroom? What counts as acceptable AI use?

At GPTZero, we work with thousands of educators across K-12 and higher education who are living through these questions. We’ve collected practical strategies from educators who are dealing with the challenges of AI right now – and we’ve gathered the most useful information below.

The State of AI in Classrooms 2025-2026

According to the Higher Education Policy Institute, student use of generative AI has only grown: in the past year, the number of students admitting to using generative AI for assessments has gone up from 53% to 88%, with most students saying they use AI to explain concepts and summarize readings.

Similarly, the number of students who declare they don’t use generative AI at all has dropped sharply, from nearly half last year to just 12% today. As one student said, “‘I enjoy working with AI as it makes life easier when doing assignments however I do get scared I’ll get caught.”

There are differing opinions on what the above means. David Brudenell, executive director at Decidr, told Forbes that AI should be dealt with in the same way that previous generations treated the calculator or the internet: an inevitably essential skill. He argues that to forbid it would be like “banning the internet in 2000 or the calculator in 1985.”

How teachers are using ChatGPT in 2025-2026

In 2024, OpenAI published guidance on how educators might use ChatGPT as a teaching support, and a model for critical thinking. In 2025, many teachers started doing exactly that, using AI as a thinking partner, instead of being a replacement for student work. Here are the most common ways they are using it, according to OpenAI.

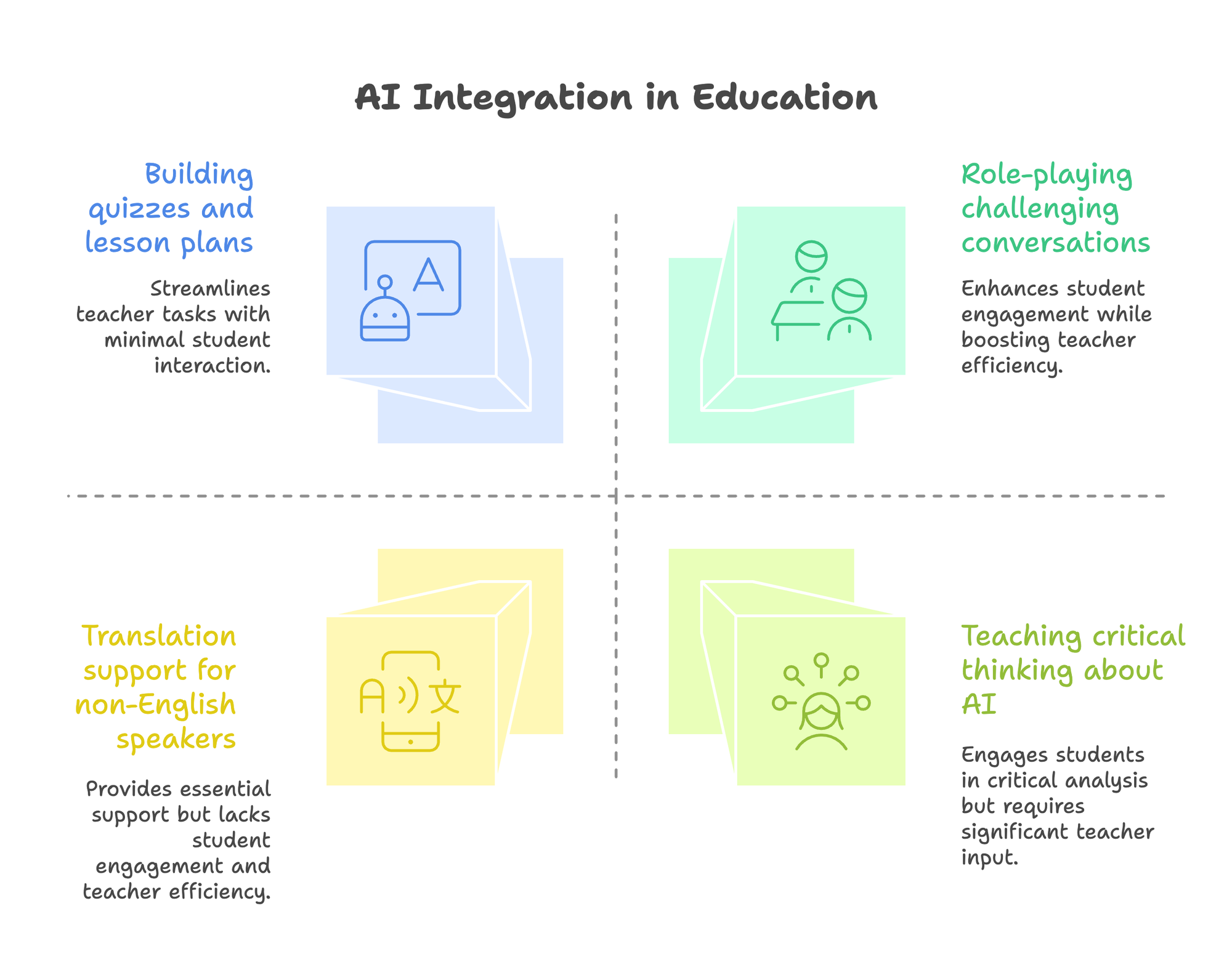

Role-playing challenging conversations

One of the most common uses by educators is role-play. Helen Crompton, Professor of Instructional Technology at Old Dominion University, encourages her graduate students to use ChatGPT as a stand-in for specific personas: a debate partner who challenges weak arguments, or a manager delivering feedback in a particular style, for example.

Exploring ideas in a conversational format helps students see their thinking from new angles; and move away from passively absorbing information, towards responding and defending ideas, which are skills that are hard to outsource to AI.

Building quizzes, tests, and lesson plans from curriculum materials

Teachers are using ChatGPT behind the scenes to reduce prep time. Fran Bellas, a professor at the Universidade da Coruña in Spain, recommends using ChatGPT as a starting point for quizzes and lesson plans. His approach is to share the curriculum first, then ask the model to generate culturally relevant scenarios or alternative question formats.

As he puts it: “If you go to ChatGPT and ask it to create 5 question exams about electric circuits, the results are very fresh. You can take these ideas and make them your own.”He also uses the tool to sense-check whether questions are inclusive and accessible for a given learning level.

Reducing friction for non-English speakers

In multilingual classrooms, AI is often being used as a language bridge. Anthony Kaziboni, Head of Research at the University of Johannesburg, teaches students who rarely speak English outside the classroom. He encourages students to use ChatGPT for translation support and language practice, especially where minor grammatical misunderstandings can have academic consequences.

Teaching students how to think critically about AI

Many educators are using ChatGPT to teach about AI itself. Geetha Venugopal, a high school computer science teacher at the American International School in Chennai, treats AI literacy to teaching internet literacy. In her classroom, students are reminded that ChatGPT’s responses may sound confident, but confidence isn’t the same as correctness.

Instead, students are encouraged to verify claims with primary sources and reflect on when not to trust the tool. The objective, she says, is to get students to “understand the importance of constantly working on their original critical thinking, problem solving and creativity skills.”

How do AI chatbots like ChatGPT work?

OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, has been working on large language models (LLMs) and “GPTs” (generative pre-transformers, a type of LLM) over the past decade. While these systems have become much more fluent and capable since their public release, the underlying mechanism is still the same: they generate language by predicting what words are most likely to come next, given a prompt and its context.

When a student types into ChatGPT something like, “Help me study for my molecular biology test,” the model is producing a response based on patterns learned from large volumes of human-written text (not searching a database or weighing the credibility of sources). This is why the output can sound authoritative and convincing, even when it’s false.

In 2025, newer models are better at maintaining context over longer conversations, and reducing obvious errors, yet they still don’t understand content in a human sense: they don’t know if something is true or original for an academic task, unless a human applies judgment. In some cases, they will confidently generate references that don’t exist, known as ‘hallucitations’.

If you need to verify references, check out GPTZero’s hallucination detector.

How does GPTZero work?

At GPTZero, our detection model has undergone third-party validation by the Penn State AI Research Lab (2024). Our work has also been cited in The New York Times, Forbes, and CNN, reflecting its recognized role in shaping responsible AI detection standards.

GPTZero uses a combination of linguistics, deep learning, and interpretability techniques, meaning our model explains the why behind results. When it comes to the nuts and bolts, many AI content detectors rely on the same techniques AI models like ChatGPT use to create language, including machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP).

Machine learning is about recognizing patterns: the more text is analyzed, the more easily the tools can pick up the subtle differences between AI-generated and human-generated content. Our ML pipeline is continually updated with outputs from the latest AI models, including GPT-4o, Claude 3, and Gemini 1.5, ensuring reliable detection of next-generation systems. Machine learning drives predictive analysis, which is critical for measuring perplexity, a key indicator of AI-generated text.

Natural language processing is about the nuances of language, and helps AI detectors gauge the context and syntax of the text it is analyzing. AI can create grammatically correct sentences but tends to struggle with being creative, subtle, and adding depth of meaning (which humans naturally use in their writing).

Within these broad categories of ML and NLP, classifiers and embeddings play important roles in the detection process. Classifiers place text into groups depending on the patterns they have learned: much like teaching someone to sort fruits based on characteristics they’ve learned, but applied to language. Embeddings represent words or phrases as vectors, which create a ‘map’ of language; this allows AI detectors to analyze semantic coherence.

GPTZero is built around explainability, and highlights specific sentences and explains why they were flagged. This approach aligns with emerging transparency guidance from organisations like the OECD and UNESCO, and it’s why many educators use GPTZero as part of a broader conversation.

How Much AI Does My School Allow? Understanding AI Policies in Education

While a few years ago, American school districts and administrators we surveyed lacked policy guidelines on what to do about AI policy, the themes for this year were that AI policies are highly local, and often rewritten from one year to the next, as the technology evolves. There is also a sense that this is a very new area, with very few fixed examples of what best practice looks like.

As one educator told us: “I am trying to find ways to get students to stop using AI for their written summaries in class and not doing any of the work themselves. Our university is not providing us with any tools to detect AI at the moment.” This shows how much of the responsibility has now fallen to individual schools (and often individual teachers) to decide what’s acceptable.

Check out our guide on creating an AI policy for your institution.

Many schools now fall into a similar pattern: while AI is largely allowed for early-stage work, like brainstorming or outlining, it is restricted or prohibited for final submissions. The emphasis is on making sure that assessed work reflects a student’s own original thinking, and that if any AI has been used, it is cited properly.

Data privacy has also become a major concern, with many schools warning students against entering personal or sensitive information into AI tools, particularly in K-12 settings where safeguarding requirements are stricter.

There’s also growing recognition that policies alone aren’t enough, with schools investing more in teacher training so staff can guide students with confidence, though comfort levels still vary widely by subject and experience, according to Digital Resistance and HEPI. In reality, a lot of the day-to-day decision-making still sits with individual teachers.

Also, the tone of AI policies is moving towards better assignment design, and more AI-resistant assessment, instead of AI use being treated as automatically suspicious, according to reports from HEPI and SMF.

How much AI should I allow in my class?

This is a common worry for many teachers today. At our first Teaching Responsibly with AI webinar, more than 3,000 educators signed up and over 1,000 joined live. Hundreds shared how they’re including GPTZero in their syllabi as part of the writing process. What stood out was that most teachers already assume students are using AI; that’s a given. The real uncertainty is about what comes next, after detection.

In the webinar, we were joined by Antonio Byrd, Assistant Professor of English at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and a member of the MLA-CCC Task Force on Artificial Intelligence. Byrd’s argument is that too many educators fall into what he calls “surveillance pedagogy,” where AI tools become a way of monitoring students rather than supporting learning. As he put it, “I don’t want to be raising an eyebrow at my students all the time, tracking and scrutinising everything they do throughout the writing process. That’s not the relationship I want.”

Instead, Byrd encourages a values-based approach rooted in engaged pedagogy, where students are treated as active participants in learning. Trust means being explicit about expectations. Byrd sets the tone from day one, sometimes quite literally, by playing music as students arrive to soften the awkwardness of the first class. As one educator shared during the webinar chat, “I don’t start with the syllabus. I start with who we are, together, and then get to the syllabus later.” That relational starting point makes later conversations about AI use feel less like interrogations and more like part of an ongoing dialogue about learning.

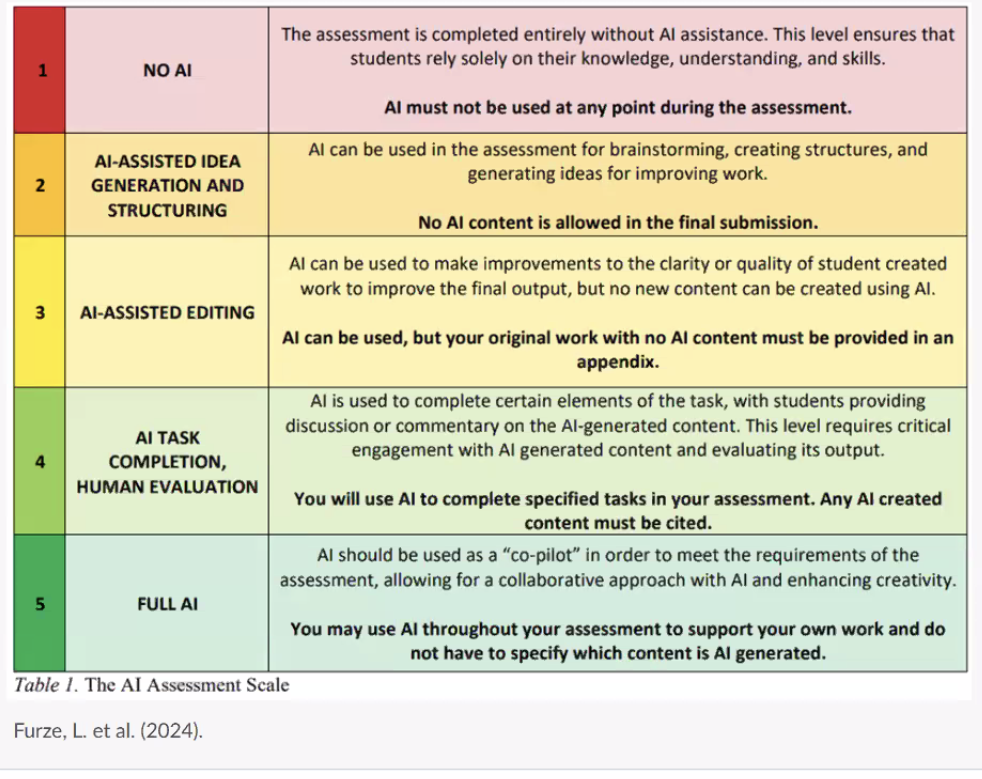

Rather than drawing a hard line between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” AI use, Byrd proposes thinking in terms of a sliding scale – and one of the frameworks he referred to is the AI Assessment Scale by Furze, L. et al (2024).

He also talks about how at one end of the scale are uses that align with learning goals, such as brainstorming ideas, organising sources, or clarifying concepts, as long as the student remains in control of the thinking. In the middle are what he calls pain points: uses that don’t necessarily violate shared values but signal a problem that needs addressing. A common example is a hallucinated source. “For me, that’s a pain point. It doesn’t necessarily ruin the whole paper, but it tells me I need to say something,” Byrd explained.

When those conversations do happen, Byrd argues they should start with listening. He draws on the idea of rhetorical listening: listening to understand rather than to respond or accuse. That means asking open questions like, “Can you tell me about your process for this assignment?” It also means recognising that defensiveness often comes from fear or confusion, not malice, and being attentive to who might feel most constrained by rigid AI rules, including multilingual students, neurodivergent students, or those already anxious about writing.

How can you tell if something is written with ChatGPT?

This has become a big concern in 2025, and as it is a more frequently asked topic, the methodology to deal with it has become more sophisticated. Let’s look at the overview of it below.

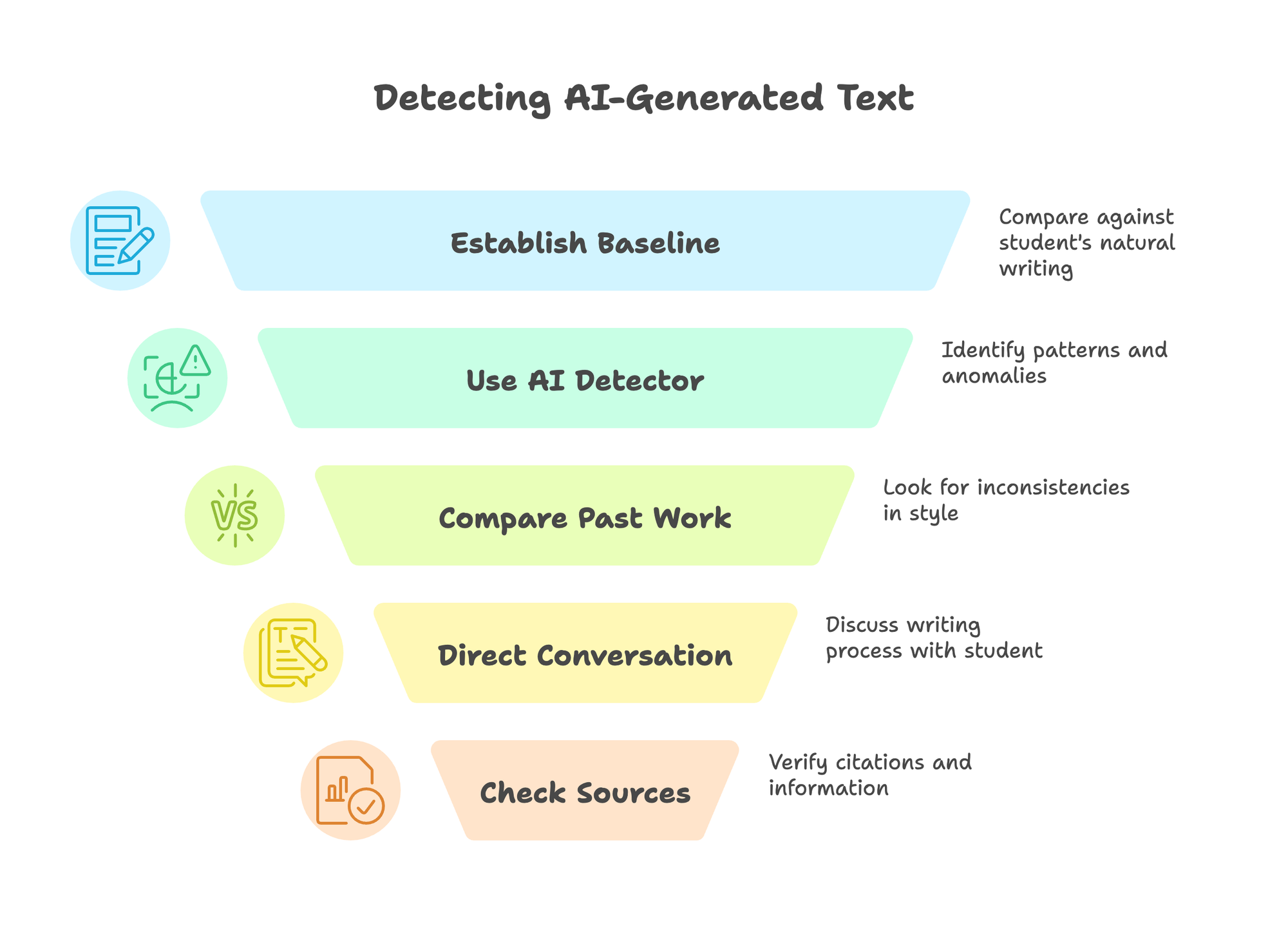

First, before you ever suspect AI use, it helps to establish a baseline for each student’s natural writing voice, and a short, in-class writing exercise without devices can serve as a snapshot. Keep this alongside earlier assignments so you have something to compare against later if a submission feels out of character, and over time, you’ll start to notice things like sentence length, vocabulary range, spelling habits, or even whether a student often makes typos.

If something does feel “off,” that’s when an AI detector can be useful, primarily as a conversation starter. Maybe the tone suddenly feels overly formal or the ideas unusually generic. Running the work through a detector like GPTZero can help surface patterns you might otherwise miss. You can also pair the scan with draft history or a Writing Report to see how the piece came together over time.

Next, zoom out and compare the work against the student’s past submissions. Does it still sound like them? AI-generated text often sounds weirdly smooth and strangely flat. Look out for repeated sentence structures, overuse of passive voice, vague pronouns like “it” and “they,” and a reluctance to use contractions.

If questions remain, talk to the student directly, and keep the tone calm and supportive, as this is an opportunity to understand their process. Ask open questions like, “Can you walk me through how you approached this assignment?” or “Why did you choose this source?” Students may be nervous and forget small details, especially if time has passed. But if they struggle to explain core choices or seem disconnected from their own argument, that can indicate the work wasn’t fully theirs.

Source checking is another important step, since AI tools are notorious for fabricating citations that look convincing but don’t exist. Spot-check references: do the publications exist, do the quotes appear in the original text, and do they actually support the claim being made? Even when sources are real, AI can misattribute information or flatten nuance.

Features like Writing Report allow students and teachers to review how a piece evolved. As Eddie del Val, who teaches at Mt. Hood Community College, has shown, bringing AI openly into the process, with set boundaries, can turn detection into a checkpoint for learning.

One educator described how they require students to draft their work in shared Google Docs, so the writing process itself is visible. Being able to see patterns like copy-and-paste activity, revision history, and the amount of time spent on an assignment gives important context. When a submission looks unusually polished compared to a student’s earlier in-class writing, they review the report more closely.

In cases where the timeline suggests the work couldn’t realistically have been written from scratch, the teacher invites the student to talk through what happened. These conversations are often enough to surface misuse, and instead of escalating immediately, the student is typically given the chance to revise and resubmit the work properly.

How do I teach in a post-ChatGPT world?

This is a topic we’re passionate about at GPTZero, but it’s a big one. As an overview, here are some of our most-used resources:

- How to Make ChatGPT-Proof Classroom Assignments: Looking for ideas on setting assignments that outsmart ChatGPT? Here, we explore the art of designing AI-proof assignments.

- Plagiarism vs. AI Plagiarism: What’s the Difference (and Why It Matters): If you’re a student trying to maintain your academic integrity or an educator working out your policies, understanding this topic matters more than ever.

- What to Do if a Student Is Using AI: Strategies for Educators. Unsure how to handle student AI use? Here’s how teachers are approaching it, with empathetic questioning and consistent processes.

Besides the above, a resource we’ve come across is Med Kharbach’s “15 Practical AI Tips for Teachers” (inspired by UNESCO guidance), which encourages educators to ask whether a given use of AI aligns with their teaching goals and genuinely deepens student understanding.

He argues that classrooms work best when expectations around AI are explicit and shared. Rather than imposing rules unilaterally, he recommends inviting students to co-create an AI use policy. Framing this as a shared agreement builds ownership and clarifies boundaries: what AI can be used for, what should remain AI-free, how AI should be credited, and how ethical issues like privacy and equity are handled.

Kharbach points to structured frameworks, such as assignment scales, to help teachers signal when and how AI is appropriate, as well as reducing ambiguity between acceptable support and outsourcing thinking.

He suggests developing a rubric for AI tools based on accuracy, transparency, accessibility, privacy, and learning value. Sharing this rubric with students turns tool selection into a learning opportunity in itself, helping them critically assess technologies instead of passively consuming them. He also talks about communicating clearly with parents and guardians about all of the above.

Overall, ethics and trust run throughout his advice, and he argues that teachers should make time to discuss bias, plagiarism, and data privacy, positioning AI as something to question and leading to ultimately more responsible AI use. Expectations and consequences also need to be fair – as one example policy puts it: “If AI is used in ways we didn’t agree on, the work won’t count and you’ll need to redo it. If it happens again, school rules on academic integrity will apply.”

Conclusion

AI tools are only going to continue to develop both in their popularity and their capabilities. Similarly, teaching styles have to continue to evolve as well. We know from our experiences that tools like GPTZero ultimately work best when they are one aspect of a broader, thoughtful approach.

We know that detection can support a teacher’s natural instincts and can help to ground tough conversations in data and context. In that sense, teaching in a post-ChatGPT world will still fundamentally be about relationships. While AI can introduce new questions around genuine learning, it is education leaders as well as educators themselves who are having to find their own answers.