AI Hallucinations: Definition, Examples & How To Prevent

AI hallucinations happen when a model confidently invents information like fake citations. Learn what causes hallucinations, see real examples, and get practical steps to prevent them.

AI hallucinations are starting to get more embarrassing and expensive (specifically, for Deloitte, almost half a million dollars.) While LLMs sound confident, it’s critical to understand what an AI hallucination is, often by examining real AI hallucination examples, as well as uncovering what causes AI to hallucinate in the first place.

At GPTZero, we’re very familiar with this issue due to our work uncovering hallucinated citations in high-stakes institutional reports and academic papers, including the Deloitte Australia report and submissions to top AI conferences. Here, we look at all of that, plus what safeguards you can put in place to reduce the risks of AI hallucinations.

What are AI hallucinations?

An AI hallucination is when a model produces output that looks like it could be true, but it isn’t. In IBM’s words, it is “when a large language model (LLM) perceives patterns or objects that are nonexistent, creating nonsensical or inaccurate outputs.”

A LLM is predicting what words are likely to follow, based on data patterns, and as a result it can create answers that sound authoritative while also being wrong. AI hallucinations tend to fall into a few broad categories.

Factual errors

These are the most common, and often the most subtle, as the structure of the answer might be correct, with one or more key details being false. For example, a model could state that a law is already in force when in reality, it might still be in the proposal stage. Or it could give you the wrong date for a historical event. Yet if the response sounds about right, it can be easy to skim through without noticing the mistake.

Fabricated content

This is when the AI goes from being slightly incorrect to actually making things up. It could involve citing academic papers that simply don’t exist, along with fake DOIs and journal names, or most commonly, linking to URLs that look legitimate but lead to 404 pages. In fact, GPTZero recently found hundreds of hallucinated citations that slipped past reviewers for the prestigious Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).

Nonsensical outputs

These are the things you’re less likely to miss, as they tend to be obviously incoherent. It could be repeating the same sentence or phrase in different ways, without ever answering the question; or mixing up concepts from different domains (e.g. “In your legal essay about impact investment, remember to log this workout in your fitness app”).

How do AI hallucinations occur?

Language models like ChatGPT, in OpenAI’s own words, “first learn through pretraining, a process of predicting the next word in huge amounts of text.” This is without ever being told which specific statements are true or false, which makes it especially hard to separate valid facts from invalid ones – even when later fine-tuning adds some labelled data.

Much like an image model can easily learn “cat vs dog” but will always struggle if you ask it to guess each pet’s birthday, language models are good at learning consistent patterns (like spelling or punctuation) but will always be shaky on arbitrary, low-frequency facts. Those hard-to-predict facts are where hallucinations naturally creep in, and later training stages can only reduce that behaviour.

Why is AI Flawed?

Generative AI can be inaccurate and biased for a few simple reasons, and MIT Sloan Technology Services (STS) outlines why AI is flawed with the following:

- It learns from a messy internet: These models are trained on huge amounts of online text, which includes brilliant research, random blog posts, misinformation, and all the usual human biases. Crucially, the model doesn’t “know” which is which; it just absorbs patterns in this big fruit salad of information. So if the training data contains falsehoods or bias (and it does), the model will happily reproduce them.

- It’s built to sound plausible, which isn’t the same as being right. Under the hood, a generative model is basically an extremely powerful autocomplete: its job is to predict the next likely word, which differs from sticking to the facts. When it gets things right, that’s a side-effect as opposed to the goal.

- It has no built-in sense of truth. These systems don’t have a mechanism for separating “true” from “false”, and even if you trained a model only on accurate information, it would still remix that material in new ways (and some of those combinations would inevitably be incorrect). The generative process itself makes error and distortion unavoidable.

As our own Senior Machine Learning Engineer Nazar Shmatko shares, “AI hallucinates when the information required to fulfill a request is missing, ambiguous, or outside of the training dataset. The model may confidently fill-in the gaps with plausible-sounding guesses.”

“This tendency is amplified by the pressure to always provide a complete answer (just try to shush any voice assistant ). As a result, when a user asks an LLM to generate a citation without sufficient context, the model may make up sources. Such misinformation can go unnoticed because AI is optimized to produce answers that sound coherent.”

Implications of AI hallucination

In most cases, when we are writing, we are imparting information – and when that information’s inaccurate or false, it’s our credibility that takes the hit. While it can be funny to giggle at AI hallucinations happening somewhere else, when it happens to us, it can be deeply embarrassing, not to mention expensive, beyond just monetary terms and reputationally as well. It can lead to three main kinds of damage:

Reputational risk: If an AI system attributes work to the wrong authors, or confidently states something that isn’t true (including a citation that doesn’t actually exist), it’s you that looks bad, not the model. Getting caught out using fake references or non-existent books undermines trust very quickly, especially in fields that rely on accuracy as a baseline (such as academia), and it can take a disproportionate amount of time to make up for any lost credibility.

Operational and financial cost: Every hallucination that makes it into production creates extra work, as teams have to re-check deliverables, issue corrections, redo analysis, and handle the fallout with stakeholders. In lower-stakes settings, it’s just annoying, but in higher-stakes environments, the time and money spent cleaning up after a bad output can easily outweigh any efficiency gains you hoped to get from AI in the first place.

Legal and compliance risk: When hallucinations show up in regulated or high-stakes domains (for example, legal summaries or internal policy docs) they can introduce real liability. A made-up case or incorrect “best practice” can push people towards decisions that breach policy or put others at risk.

Why are AI hallucinations a problem?

Besides the above, hallucinations can also affect the broader knowledge ecosystem, and slowly dilute the very definition of accuracy. As GPTZero’s Head of Machine Learning Alex Adam says, “Even if a paper using hallucinated citations isn't ‘slop’, it can have negative impacts on the research community. Claims made in the paper relying on non-existing sources will be used to inform future works, misleading other researchers.”

Specifically, there is a risk that those researchers then go on to continue misleading other researchers, and so on. Adam explains, “‘An excerpt in a paper like "Jane Smith et al. established that…’ is harmful because the reader will take it at face value, leaving out the skepticism they might have for obvious slop.”

Try GPTZero’s Hallucination Detector to validate sources in seconds.

Examples of AI hallucinations

So what do AI hallucinations actually look like? We’re familiar with this because GPTZero has used our Hallucination Check tool to uncover 50 hallucinated citations in papers under review for ICLR 2026. We've also tested it on the scandal-ridden Deloitte Australia report, and hundreds of other documents, as well as a sample set of 300 ICLR papers submitted to OpenReview. There are also some viral examples from around the web.

The Deloitte Australia report

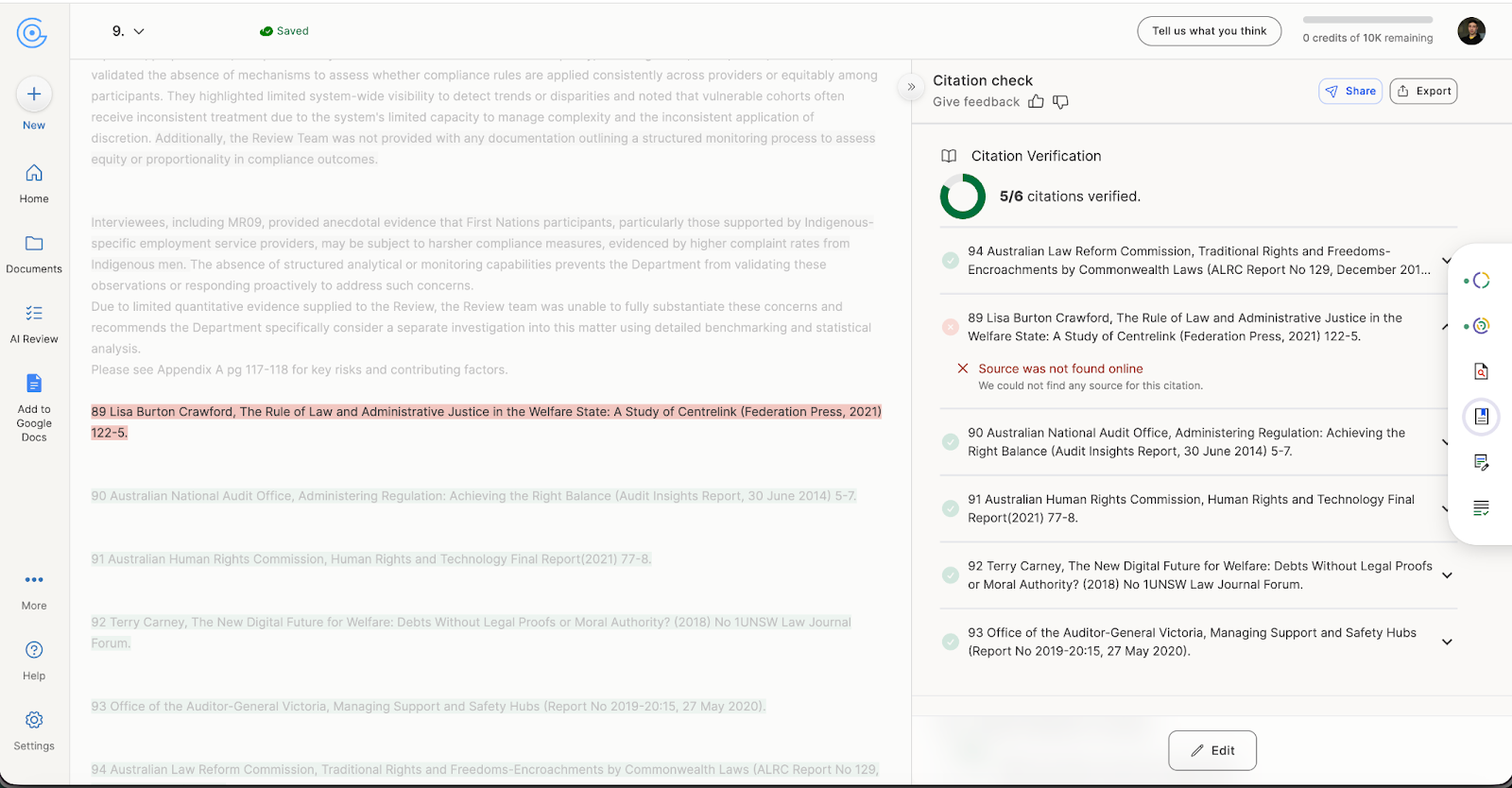

Deloitte’s original version of the report contained 141 citations. Citation Check identified more than 30 issues with these citations, including 20 probable hallucinations. For example, this scan of Chapter 9 indicates that citation 89 is fake.

“You can see this table with all citations we found to be hallucinated, which were verified by a historian PhD expert on our team,” Nazar and the authors explain. “Unlike humans, LLMs are extremely good at fabricating well-formatted references with plausible authors and titles. Because humans associate well-formatted citations with domain expertise, the skills displayed by an LLM lull us into thinking the cited claim is well-supported, especially since verifying citations is tedious.”

ICLR 2026 papers

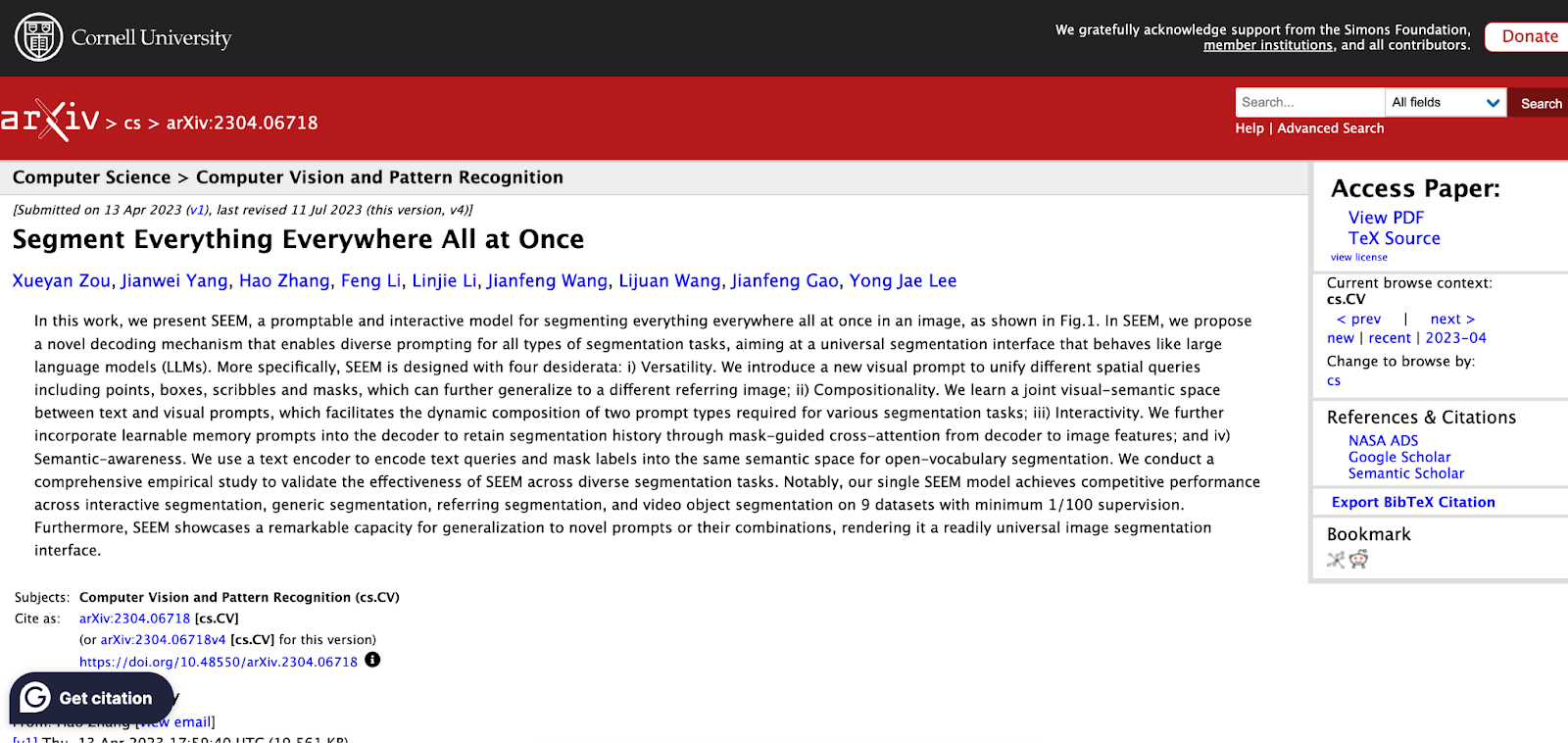

There are the hallucinated citations in papers under review for ICLR 2026. In TamperTok: Forensics-Driven Tokenized Autoregressive Framework for Image Tampering Localization, one of the papers cited is:

Chong Zou, Zhipeng Wang, Ziyu Li, Nan Wu, Yuling Cai, Shan Shi, Jiawei Wei, Xia Sun, Jian Wang, and Yizhou Wang. Segment everything everywhere all at once. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), volume 36, 2023.

While this paper does exist, every single one of the authors are wrong. In the correct version, the authors are Xueyan Zou, Jianwei Yang, Hao Zhang, Feng Li, Linjie Li, Jianfeng Wang, Lijuan Wang, Jianfeng Gao, and Yong Jae Lee.

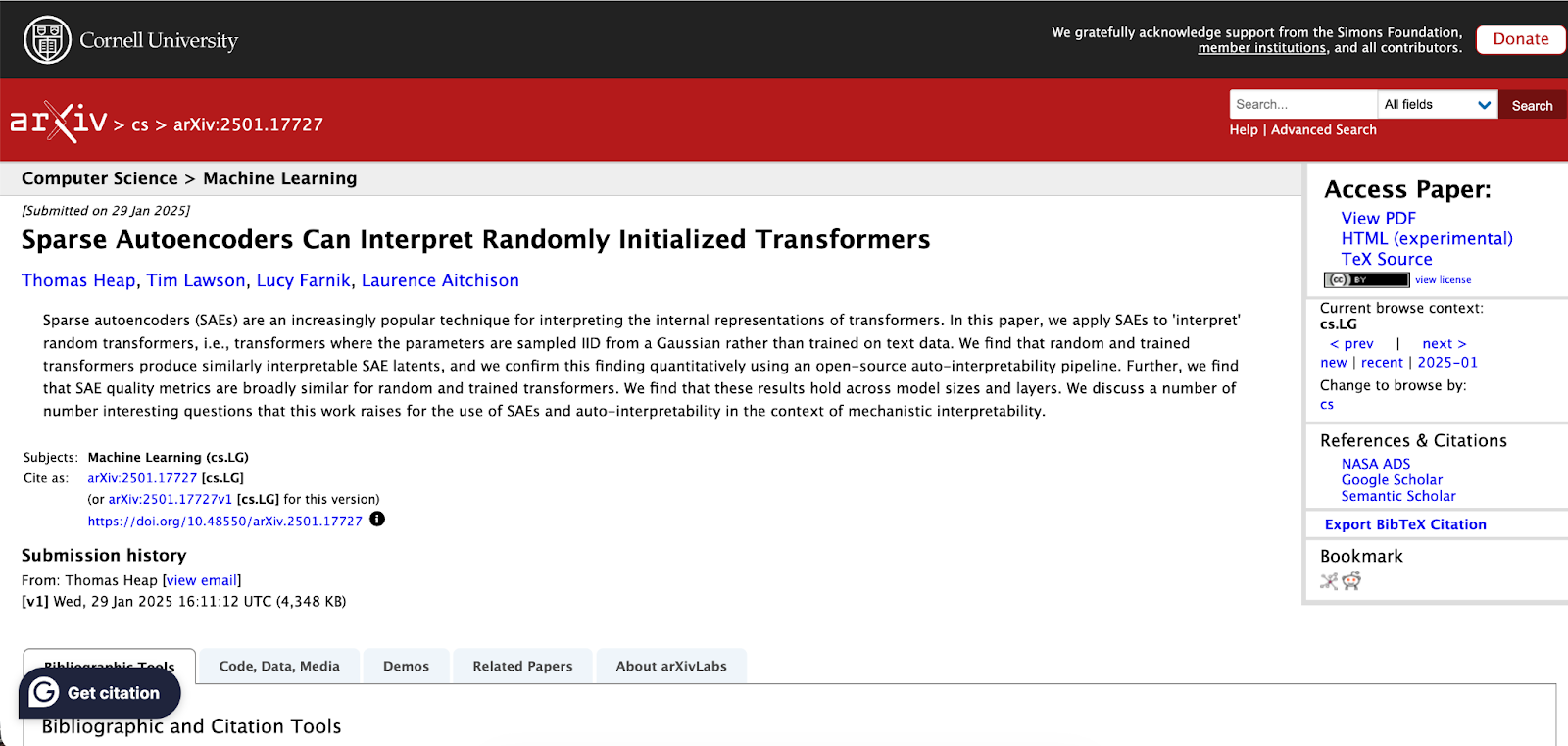

The same thing happened in OrtSAE: Orthogonal Sparse Autoencoders Uncover Atomic Features, where it cited:

Robert Huben, Logan Riggs, Aidan Ewart, Hoagy Cunningham, and Lee Sharkey. Sparse autoencoders can interpret randomly initialized transformers, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/ abs/2501.17727.

Again, this paper does very much exist, but all authors are wrong. The correct authors are Thomas Heap, Tim Lawson, Lucy Farnik, Laurence Aitchison.

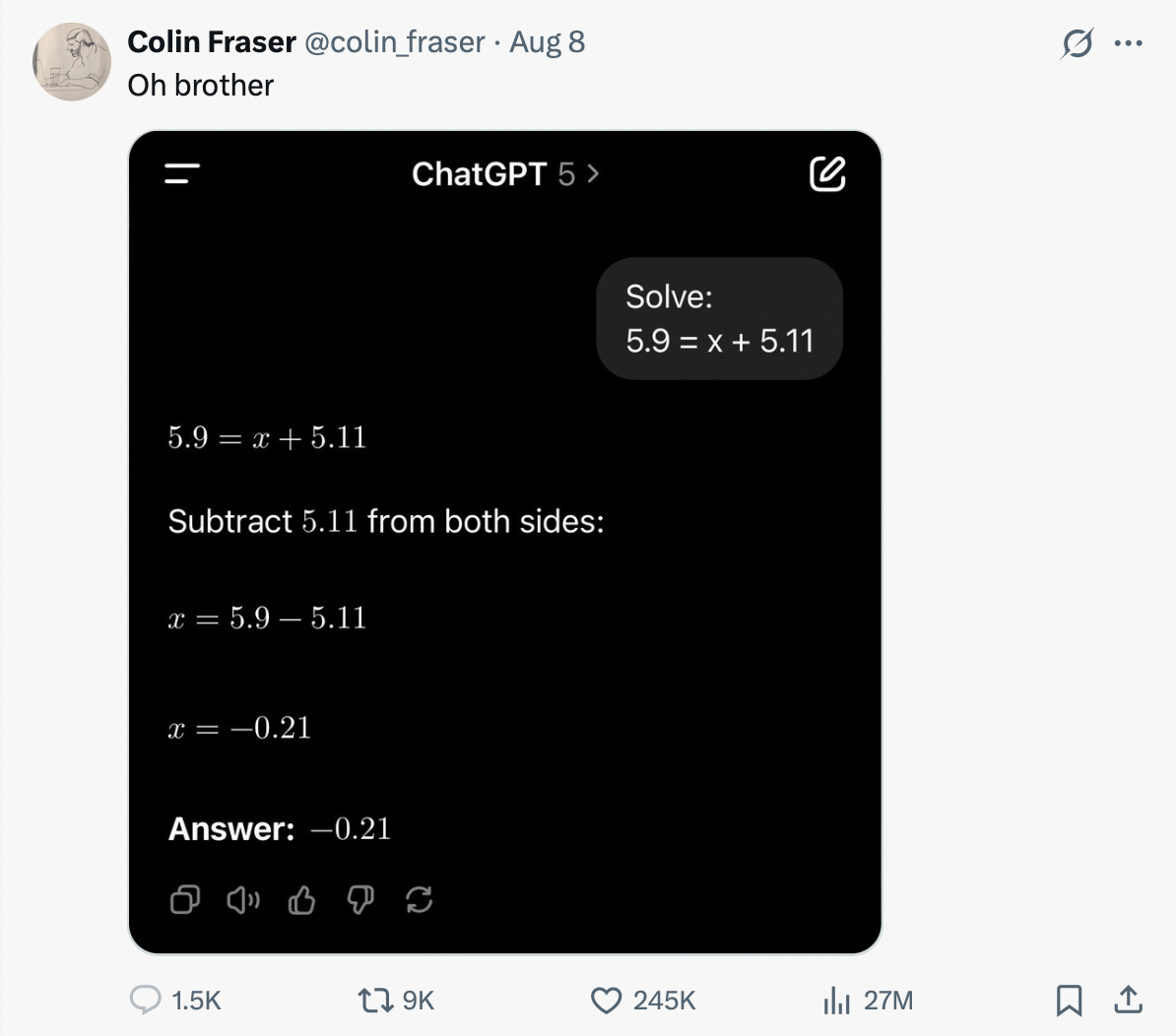

Math fails

Most LLMs are still pretty bad at maths: they look like they can do multiplication and division, but are just predicting the number that seems most likely based on their training data. Newer state-of-the-art models do better on simple, one-step problems (like 17 × 24), but they still fall down on multi-step reasoning, which is exactly how you end up with an answer that’s beautifully explained and is still wrong, like in this example:

The Summer Reading List

Last year, Chicago Sun-Times readers opened their paper to find a “Summer Reading List for 2025” that included fake books attributed to real authors. Only 5 of the 15 titles were real while the rest were AI fabrications with convincing blurbs. Chilean American novelist Isabel Allende has never written a book called Tidewater Dreams, even though the list billed it as her “first climate fiction novel.”

Likewise, Percival Everett, who won the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, has never published a book called The Rainmakers, supposedly set in a “near-future American West where artificially induced rain has become a luxury commodity.” The paper later said the list came from another publisher, which admitted it had used AI to generate it, and the online version was removed.

Yep- the bogus summer reading list from the Chicago Sun Times is real. Here I am with it from a few minutes ago. (Support your local library!!)

— Tina Books (@tbretc.bsky.social) 2025-05-20T15:01:01.631Z

How to prevent AI hallucinations

While it’s not possible to completely eliminate the risk of AI hallucinations, it is possible to minimize the risk. We like these suggestions from Zapier on how to do so.

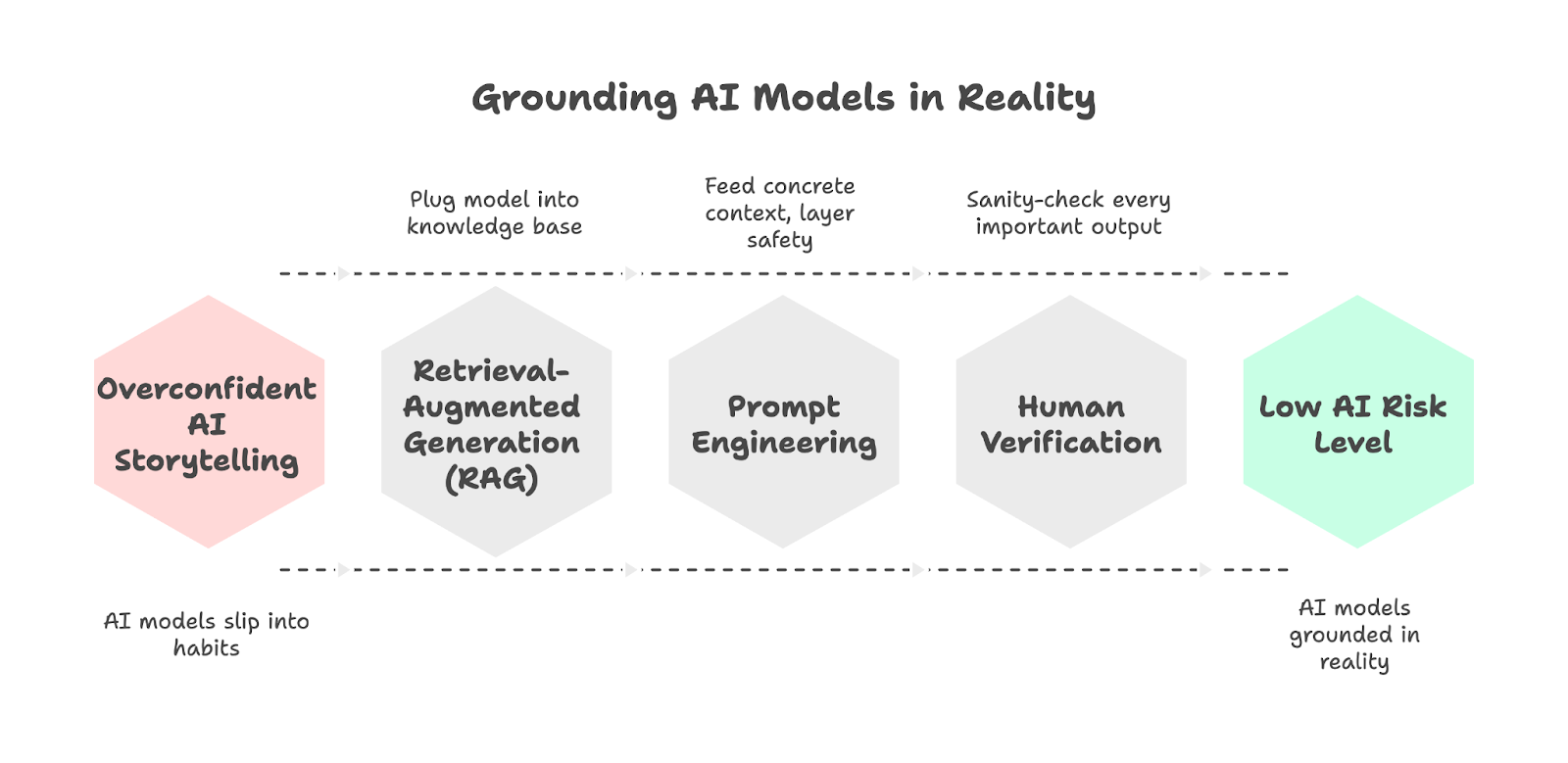

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is one of the main ways teams ground models in reality. Instead of asking a model to “remember” everything, you plug it into a trusted knowledge base (e.g. case law or your internal wiki) so it can pull actual documents and then generate answers from those. When you do this effectively, tools can accurately cite actual cases or policies, although RAG still can’t get rid of hallucinations entirely and also has its own implementation hurdles.

Prompting engineering also matters a lot, and your results will massively improve if you use specialist tools for specialist jobs, feed the model concrete context (documents, data, references), and layer on safety habits: fact-check anything high-stakes, use custom instructions and temperature controls where available, ask the model to double-check its own work, break complex problems into smaller steps, give clear single-step prompts, and tightly constrain the formats or choices you want back.

In the end, “verify, verify, verify” is the only real way to make sure the risk level stays low. Even with better training, RAG, and smarter prompting, these machines can still slip into a habit of overconfident storytelling. At the end of the day, you still need a human in the loop to sanity-check every important output.

Conclusion

Hallucinations are far from a quirk and are best seen as a structural limitation that come with today’s LLMs, which are at best pattern-matchers that make things up from time to time. The risk cannot be entirely eliminated but it can be minimized when you use tools like GPTZero’s Hallucination Checker to verify sources, and most of all, treat hallucinations less as a random surprise and more like a potential hazard of using AI.

Scan a document with GPTZero’s Hallucination Detector to verify claims.